Thoughts on True Detective

What is this show trying to say?

Note: this post contains spoilers for the recently concluded third season of True Detective.

“What if the ending isn’t really the ending at all?”

The recently aired third season finale of True Detective is obsessed with this concept. Irresolution as resolution, so to speak. Wayne Hays, our protagonist, has been haunted by the same case for thirty five years. It has broken him. It has consumed him so much that he has become little more than a hollowed out, lonely man, struggling with a deteriorating mind. He finally, finally hears the truth that he and thus us in the audience have been waiting for. It better be good, right? It has to be good, or else the internet will complain that we wasted eight weeks of our lives.

It isn’t good. It’s profoundly underwhelming. That’s the whole point.

Throughout this season of True Detective, series creator Nic Pizzolatto (who is credited as a writer for every episode) seems interested in the season’s case, of missing children and the deeply sinister motivations behind this, largely as a lens for character exploration. A feeling I often had while watching the previous episodes was that watching the rise and fall of the Hays marriage was proving much more compelling material than the case. The finale reframed this as a deliberate tool. The questions the season is interested in are that of the toll an unsolved mystery takes on the detective tasked with solving it. The mechanics of the thing are almost irrelevant. Having Junius Watts simply sit down and read the “Disappearance of Julie Purcell” Wikipedia article to Wayne and Roland underlines that the show never really cared about what happened to her. It was just interested in what her disappearance did to Wayne.

Wayne and only Wayne, that is. This has become a theme in the first and third seasons of True Detective (the second tried something radically different, and failed at it almost completely), helping set it apart from much of television. Serialised TV can trace its history through many forms, but certainly a key influence (and perhaps an underappreciated one) is that of the soap opera. What soap operas are built on is endless narrative, cliffhangers, and a vast array of characters and plots in a given setting that will often never intersect. One of the most influential serialised programmes of all time (and a big influence on True Detective), Twin Peaks, very openly had one foot in the soap opera genre. Most of the post-Sopranos serialised dramas have, even if they claim to be focused on a singular journey, followed the soap opera model of dealing with multiple characters’ internal narratives. Something like Breaking Bad, for example, was primarily about Walter White’s arc, but still found plenty of time to see things from Jesse, Skyler, Hank and even Marie’s perspective. True Detective does not work like that. This season is pondering Wayne’s journey and Wayne’s alone. The other characters exist only as he sees them. The idea of “novelistic” television is a ridiculous cliche, an attempt to make a medium once consigned to low brow culture feel legitimate, but True Detective does have a stronger claim to it than most in the way it really focuses in only on key perspectives.

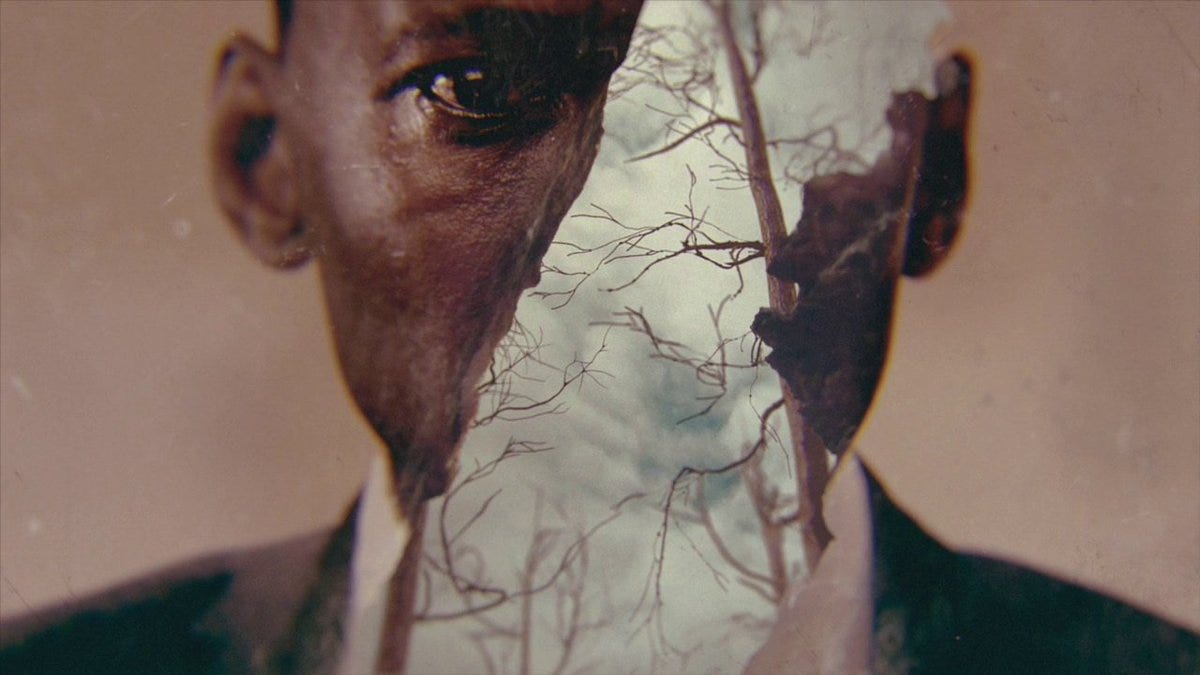

But what mileage it gets out of this one man. The use of multiple timelines initially felt like something of a gimmick, an attempt to recall a popular element from the first season but bigger and better (“this time, there are three timelines!”), but it became clear this was something much more significant. The Wayne of 2015 is experiencing dementia severe enough that he can no longer be completely sure how he arrived at any given place, with his mind skipping through his life. The fairly complex timelines thus serve as an unspooling of his life story, jumping through significant moments, skipping over important details such as the fate of his life, largely in an unclear manner. In some respects, it feels akin to the BoJack Horseman episode “Time’s Arrow”, in which Beatrice Sugarman holds on to memories of the past as the present is slipping away from her. Wayne is a man who once found himself with everything he wanted: a fulfilling career alongside a loving wife and children. Over the course of the case holding a grip on his life, this has all disintegrated, but he can’t piece together quite why.

The most persistent criticism the series received in its first two seasons was over the kind of perspectives Pizzolatto centres. Season one observed not just two white men, but two very conventional, though critiqued ideas of masculinity. This study of masculinity is, as his harshest critics would claim, all that Pizzolatto knows how to write about. Season two spent a lot of time with Rachel McAdams’ character, but she was herself a very masculine idea of a detective who happened to be a woman. Pizzolatto is interested in masculinity, exclusively, regardless of who it shows itself in. Mahershala Ali’s Wayne is, simply by virtue of casting, a departure from that. It has been stated by those involved that the character was not originally envisioned as black until Ali was hired. This feels almost impossible having seen the season. Perhaps that is purely down to Ali in making the character so distinctly his. We’ll never know.

Even in cases where one would think he would have more to say, he keeps the focus on Wayne. Carmen Ejogo’s Amelia, Wayne’s wife, is a writer of nonfiction crime books with very literary interests. She describes her book as being less about the case itself than “the town”. Wayne, however, has no interest in writing, reading, or anything in that area. Considering Pizzolatto’s own career path, it’s fairly obvious who he would side with on this, but the show still doesn’t have an interest in Amelia beyond what she means to Wayne. As limiting as this can be, I would still argue that this is more of a feature than a bug as it allows for a very close reading of Wayne, though of course it would be great to see more television shows doing the same for characters like Amelia.

But True Detective will likely never be that show. For better or worse, it is straight from the mind of Pizzolatto. In its worst, least inspired moments, it shows itself as Pizzolatto’s spiteful response to various lines of criticism he’s received over the years. A particularly bad example of this comes early in season three, when a young white woman journalist, Pizzolatto’s caricature of all his feminist critics, talks about “intersectionality” as the black man he made up rolls his eyes. This does get at a thing he is very interested in, which is answering his critics. Season two, with its labyrinthine plot dealing with the hellscape of modern inner city Los Angeles, proved to be utterly confused about what it was supposed to be saying. There, it appeared as though Pizzolatto wanted to address a central argument from those who didn’t like season one on the grounds that the plot was too straightforward. Personally, I would argue that the first season’s power came from using a very simplistic narrative framework to help ground the audience through some of its more esoteric ideas and imagery. Nonetheless, Pizzolatto seemed to feel that he had a point to prove in showing that he could write a complicated case. This backfired enormously, as season two became a widely panned punchline. Season three thus feels like an attempt to strike a balance, to keep things relatively straightforward and still find a complex arc. It doesn’t quite hit the highs of season one. That season had not just a great core character but a great relationship, with Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson both elevating each other to career best work. It also had the magic ingredient of Cary Joji Fukunaga, who seemed comfortable at times diverting from Pizzolatto’s intentions on the page and McConaughey’s character in a much more negative light, directing all eight episodes. While it lacks in these places, the third season is certainly the best the show has ever been narratively, finding a weave a complex structure in without massively over-convoluting things.

There are also questions about the way the case of the season, admittedly in the background, alludes to far right conspiracy theories about paedophile gangs. Pizzolatto’s likes on Twitter suggest he has at least some sympathy for conservative political positions. Yet this feels in conflict with the show’s critical, almost at times feminist sympathising, critiques of masculinity. He can be a complicated person to read at times. Perhaps this opaqueness is a part of what makes True Detective such compelling television. I don’t know what else is on Nic Pizzolatto’s mind. Some of it will delight me. Some of it will probably infuriate me. But either way, I can’t wait to see what he comes up with next.