The Curious Worldview of Michael Schur's Television

Why won't these shows click for me?

There probably isn’t a showrunner who earned more acclaim across the last decade than Michael Schur, creator of Parks and Recreation as well as The Good Place. It’s not hard to see why.

Episodes like “Flu Season”, “Andy and April’s Fancy Party”, “Leslie and Ron” and “Michael’s Gambit” rank among some of the best the medium has ever produced. Schur has been at the forefront of TV’s return to comedy that feels emotionally rewarding as well as laugh out loud funny, and there’s no doubt he’s one of the best at doing it. His work feels timely, too, with Parks evoking the Barack Obama era better than any other work of pop culture, while Good Place subsequently speaks to the much dicier moral questions we must ask of ourselves in this more fraught time. And there’s real attention to the structure and rhythms of the TV sitcom, too. In an era where so much TV infuriates me with its lack of care toward the craft of this specific medium, Schur is a master of it. I should be his biggest fan. This should be an article raving about his work, and mourning this week’s end of TheGood Place. But it’s not.

For all that I enjoy and respect so much of what Schur has done, there’s something about his work that always feels hollow to me. It’s taken me a long time to figure out what that is, but I think I have a more coherent idea of it now.

After serving as a loyal lieutenant to Greg Daniels on the American remake of The Office, Schur got his shot at the big time in 2009 with Parks and Recreation. Though co-created by Daniels, it was always understood that Schur was to be the showrunner, the central creative voice, of the Amy Poehler starring local government themed sitcom. Premiering in 2009 at the start of Obama’s first term as U.S. President, it very much feels forged in the shadows of the 2008 Democratic primary, a bruising affair in which presumed frontrunner Hillary Clinton struggled to compete with the eventual winner’s unique ability to mobilise voters on a message of genuine hope built atop of pretty moderate policies. Protagonist Leslie Knope is every bit the Clinton analogue, a fierce advocate for the system and its power to improve peoples lives complete with difficulties in communicating this to the public, with a limitless work ethic and a deeply ambitious streak. As part of its attempts to mirror American politics in a small town parks and recreation department, she is pitted against her boss Ron Swanson, a deep sceptic of government on the grounds of his free market libertarian views, representing the kind of counterbalance to Leslie’s Clintonite big government liberalism traditionally seen in Washington. Leslie’s party affiliation is never outright stated, and Ron would certainly reject the Republican label, but there’s no real doubt that these characters represent the two major forces in American politics.

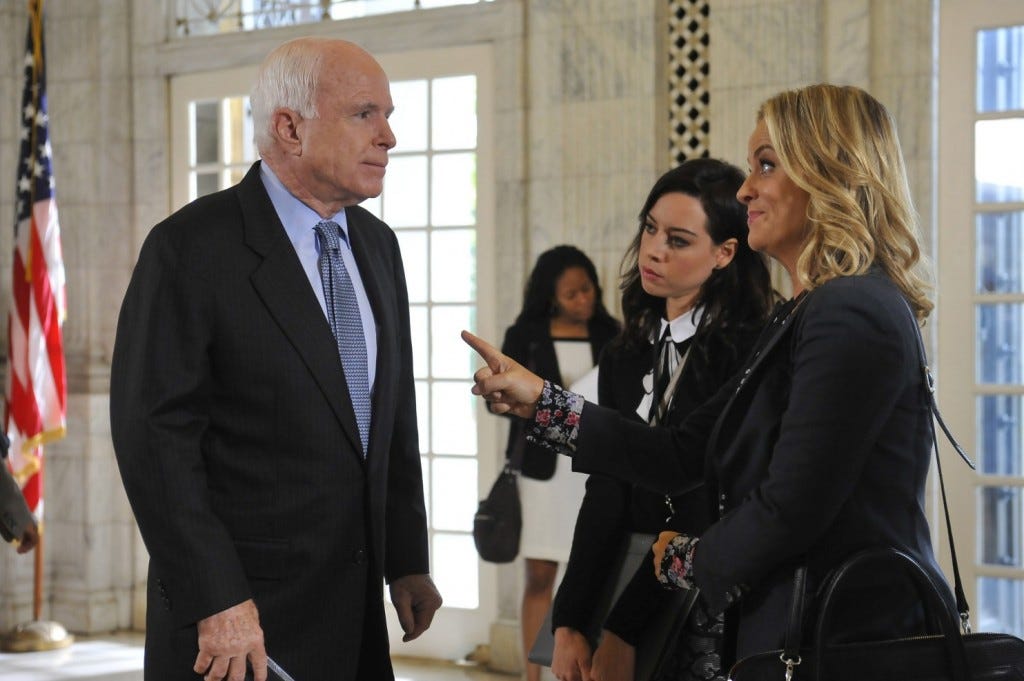

And yet, for all that the show had a political nature, it stayed fiercely apolitical in addressing real world figures. Leslie respects Democrats and Republicans equally when it comes to the women in politics she considers her heroes. Photographs of Nancy Pelosi and Condoleezza Rice take equal pride of place in her office. An early episode of the show features Leslie messing up, and she subsequently feels she has failed all women in politics. “I realise I have let down every female public official in America”, she states, “and I would like to apologize to them, right now, individually, and in alphabetical order”. We only hear her mention a few names before the show cuts away, but the choice to show her apologising to the first woman she brings up is certainly noteworthy.

“Michele Bachmann, Republican, Minnesota. I am sorry”.

This episode, season one’s “Boys’ Club”, aired in April 2009. In March 2008, Bachmann had called climate change “all voodoo, nonsense, hokum, a hoax”. In October 2008, she had raised the question of whether Obama had “anti-American views” in a very obviously racist tirade. This doesn’t seem to particularly matter to Leslie or to Parks in its championing of women in politics. Nor does the scene, even at a point in the show’s run when Leslie was shown as far less than perfect, particularly satirise this sentiment. The show has a particular flavour of liberalism at its core: the system is capable of great things, American politics is the best kind of politics, and Republicans are part of American politics so they must be good.

Parks really found its footing in its second, and best, season. Previously something of a cynical show, it opened itself up to a more upbeat take on the characters, and managed to get the balance just right between optimism and scepticism. Its sheen of realism was turned down a notch, really embracing a Simpsons-esque small town vibe, with Pawnee becoming the closest thing we will ever see to a live action Springfield. Minor characters like Joan Callamezzo could absolutely feel at home in that iconic show. What’s more, Leslie and co felt like an authentic part of Pawnee, just as capable of being absurd as anyone else in the town.

But then something started to change. The show became an increasingly warm hearted affair towards the series regulars. Mark Brendanawicz, the character least likely to go along with Leslie’s bold ideas and general sunniness, was written out of the show, to be replaced by the more easy going Ben Wyatt. The series was increasingly structured around Leslie’s big accomplishments, first the Harvest Festival then the city council election. The characters became increasingly defined by their likeability rather than their flaws. There is nothing wrong with this. Depicting hopeful, positive visions of the world is every bit as authentic as cynical ones, and I’d take Parks’ warm embrace of its characters here over the empty nihilism of something like Joker every day of the week.

The problem is just where the series allowed its optimism to be directed. With the main characters increasingly becoming the best, most likeable versions of themselves, there was no shortage of warmth in the Parks department. But for serialised storytelling in which the heroes triumph over adversity, and even just for telling funny jokes, conflict is always necessary. You cannot remove conflict from good storytelling; you can only shift it around. And so, with little of it coming from the characters themselves, Parks had to rely on external forces to create tension. As our friends in Pawnee became nicer and nicer, the town got meaner. While Leslie shown more and more to be a superhero, a uniquely great person, Pawnee at large came to hate her for no good reason the show could articulate. The recall vote, in which the public chose to remove the greatest person on Earth from office while keeping a bunch of clowns and crooks, underscored the central view of the show at this point: Leslie good, Leslie’s friends good, normal people bad.

It’s not innately a problem that Parks poked fun at small town people and values. For a show this political in nature, airing as the Obama era was met with a loud reactionary backlash that eventually led to Trumpism primarily in places like Pawnee, they had to say something about it. And there are few targets more justly deserving of vicious satire than the crank right that has come to take over much of global politics to devastating consequences. But Parks never had any serious structural critique of this. There is no Rupert Murdoch in Parks, no Koch brothers, or any clear nefarious outside capital poisoning the well for personal gain, as is the case in the real world. The town has a clear media structure involved in disseminating nonsense, with key figures such as Joan, Perd Hapley and Shauna Malwae-Tweep. But the Pawnee media seems to act largely autonomously from the outside world, insulated from the realities of private equity buyouts and corporate owners interested in pushing far right propaganda. In the absence of any kind of wider structural forces pushing people in these directions, the Pawnee general public just come across as failed by their own stupidity and sexism in their failure to recognise Leslie’s greatness.

And this was the only real conflict the show was interested in serving up. Whenever there would be a political difference between Leslie and the town, Leslie was always right. This might have been an inevitable consequence of the choice to make ordinary Pawneeans the face of Fox News watching, Tea Party supporting backwards America, but that’s an artificial constraint the show put on itself. There could have been sections of the town that thought differently. Leslie was oblivious toward race in the first two seasons (it was a running joke that she thought Tom was born in Libya), and could this not have affected her judgement as a politician? Could she not have learned from getting something wrong, and subsequently listening to people of colour in Pawnee? The show was never interested in finding out. It liked Leslie too much to ask the question.

This combination of adoring its characters and resenting everyone else denied them real chances to be challenged. If Leslie had genuinely failed in her city council role, if she had made a genuine mistake as we all do from time to time, the recall vote arc could have been that much more powerful. You can’t build arcs about triumphs over adversity if the adversity doesn’t feel like it has any teeth. This was repeated among many of the other characters, where the audience would be told of their accomplishments without ever really presenting the sense that they had to work for it. Andy tried his hand at being a children’s entertainer and quickly became the best at it in Southern Indiana. Ron started a building company that had huge, overnight success. Parks would rather reward the people it liked for being pure of heart than show the practical realities of governing or accomplishing things.

Take the episode “Animal Control” for example. In this outing, the Pawnee animal control department is in need of a new director, and Leslie’s incompetent colleagues just want to prop up one of their friends. “This whole place runs on dibs”, claims Jeremy Jamm, Leslie’s nemesis. As the embodiment of what good government can look like, Leslie argues for a proper open interview process, and gets her wish. The candidates, though, are the kind of feckless Pawneeans the series loved poking fun at, so the process is a bust. But, as usual, Leslie has an ace in her back pocket: her friend April. They have to reconfigure the government structure a bit, but April is given the job after Leslie pushes her into it. We then cut to Leslie delivering the following speech to the camera:

“Government shouldn't operate based on personal favors. It should operate based on good ideas. April had the best idea, and today the best idea won.”

At no point does the show seem to at all acknowledge that Leslie simply did a personal favour to her friend, just as Jamm intended to. Leslie’s nepotism is just common sense, justified by her pals being the most wonderful people in the world. Everyone else’s nepotism is blatantly a disaster. It’s not corruption in Parks if our friends are behind it.

A similar occurrence happens in “Fluoride”. This time, Leslie and Tom are trying to get fluoride into the Pawnee water supply for the obvious health benefits it brings, but face fierce opposition from the town’s dumb-dumbs. As the Sweetums corporation launches a flashy campaign to privatise the water supply, Leslie and Tom respond with their own flashy marketing. Fluoride is rebranded as “H2Flow”, an “app for your teeth”. That our characters essentially con the town into accepting a chemical change to their water supply (even a clearly positive one) is never really a criticism thrown at them. The ends justified the means.

There is one character, of course, who doesn’t get this treatment. Jerry Gergich, real name Garry Gergich, is something of a running joke for the characters. Largely starting in season two, it became a running joke that everyone else in the Parks department would be amused by his ineptitude and often just his general presence. As the show generally became nicer towards its heroes, though, their jokes at his expense became strangely crueler. Jerry suffers a heart attack and everyone just seems desperate to make jokes about how he farted at the same time. April steals his inhaler, a very serious matter due to his asthma, without ever giving it back, and at no point does the show treat this as inappropriate behaviour. It’s just a joke that he could die without it. In many ways, Jerry’s contentedness with his middling life in Pawnee made him the face of the ordinary townspeople in the office, and the show just couldn’t resist humiliating that, despite consistently being shown as a good person. That the writers’ solution to this was to give him a hot wife and a huge dick is hardly an excuse for workplace bullying. Parks never saw Jerry as fully human. He was their pet.

There’s a very famous quote from George R.R. Martin about J.R.R. Tolkein and Lord of the Rings that I think has relevance here, so I’ll just run it in full:

“Ruling is hard. This was maybe my answer to Tolkien, whom, as much as I admire him, I do quibble with. Lord of the Rings had a very medieval philosophy: that if the king was a good man, the land would prosper. We look at real history and it’s not that simple. Tolkien can say that Aragorn became king and reigned for a hundred years, and he was wise and good. But Tolkien doesn’t ask the question: What was Aragorn’s tax policy? Did he maintain a standing army? What did he do in times of flood and famine? And what about all these orcs? By the end of the war, Sauron is gone but all of the orcs aren’t gone – they’re in the mountains. Did Aragorn pursue a policy of systematic genocide and kill them? Even the little baby orcs, in their little orc cradles?”

Parks often feels like it has a slightly tweaked version of this: that if the politician was hard working, intelligent and capable, the land would prosper. It’s not without politics in its battle of the crank right idiots against the liberal technocrats, but that is the only political conversation that exists. The show often seems to want to take politics out of government, having “sensible” and “nonsensical” positions a lot of the time. Really, Schur and his show lacked any real structural critique of the problems it highlighted in modern small towns beyond “competence”, and it looked like he’d never develop one. Until he sort of did.

In the stunning first season finale of The Good Place, Schur gave us what might be the most terrifying concept I’ve ever seen on TV.

After a season in which the audience was led to believe the characters were in a version of heaven, the truth came out that we were, in fact, watching them being tortured in hell. The fake “Good Place” was a set up by the demon Michael (ha ha) in order to test his radical new theory: the best way to torture humans was to get them to hurt each other. Psychologically. That no amount of hell demon ideas could ever punish people the way they harm each other. It’s a truly scary concept of evil, one that ranks as darker than what so much of the horror genre has been able to produce.

It’s too bad, then, that the show has spent the next three seasons running scared away from this at every turn.

Schur’s central conceit in Good Place is about flawed people trying to make themselves better. This fits with the striver mythos in his work. Parks was famously about “turning pits into parks”, and this was mostly shown through the characters’ career progression. Here, he takes the same approach but around the much more existential problem of trying to be a good person. In a way this is retrofitted into the same career progression model as Parks. As Leslie fought to get onto the city council, Eleanor Shellstrop fought to get into the real Good Place.

And it’s here where some of the same issues come back to grate. Schur just can’t seem to resist falling in love with his characters, and when he does this, he makes them better people very quickly. Michael is the most frustrating example of this. His arc in the second season is about putting his hell demon days behind him and maturing into a moral and good “person”. But there’s remarkably little conflict or tension in this; it just sort of happens. Once Michael has decided that he doesn’t want to be evil anymore, it takes just a couple of ethics lessons before he’s fully reformed. In Schur’s world, if one of the main characters wants something enough to put even a little effort into it, they generally get it pretty easily.

And despite the premise of the show centring on these people being “bad”, they have been shown over time to be not just good, but better than everyone else. Eleanor and Jason are both from backgrounds with a lot of “bad” people, but when they revisit these places in the third season, there’s something subtly noticeable. Eleanor is depicted as slightly more real than her cartoonish friends, her accent slightly less heightened, overall feeling more like an actual human being. What made it worse is that the way the show looked at her friends was to put them in outfits coded as “trashy”, cheap and revealing, to have their greatest sin be their class connotations and sexuality. A similar effect seems to happen with Jason’s friends and family, in which all the qualities the show generally picks up on about him are more extreme in those around them. I understand that one off characters cannot be developed as much as series regulars, but there’s something really frustrating about art that makes the lead people feel more real than the world around them. It creates an illusion that there are normal people and then there are great people.

For a show about hell, Good Place has no real concept of evil. In the episode "Rhonda, Diana, Jake, and Trent", the gang visit the Bad Place, and what they find is the darkest vision of hell this show has to offer: mildly annoying stuff to TV writers. Eternal torture in this show consists of stacks of New Yorker issues you’ll never get to, Taco Bell, and the Transformers movies. With the scale of genuine suffering taking place within driving distance of the show’s writers’ room, let alone around the world, to codify the darkest pits of evil with mild first world problems of a comfortable existence feels like cowardice at best and “let them eat cake” disregard at worst. A lot of the show’s comedy comes from godlike eternal beings’ interest in contemporary American culture, and it’s not my favourite source of humour. When it goes wrong, it can imply a lack of legitimate existence outside of these bounds that feels disturbing.

Good Place again pulled the rug from under the audience’s feet in the third season, and in a way that genuinely seemed to address many of my criticisms of Schur’s work. The twist this time was that all humans in the modern world are sent to the Bad Place, owing to the increasing complexities of life making it harder and harder to do the right thing. There’s no doubt that the concept of neoliberal capitalism’s ethical quandaries making it impossible for anyone to have a net positive impact on the world is a powerful one. What’s more, it justifies so much of the show’s previous blindness toward big picture structural problems that were also absent in Parks. But again, it doesn’t feel like Schur has fully committed to this. Good Place has gone back to the points system, seeing value in keeping score, but merely tweaking the bounds to what it represents. It really does believe in the idea that people can be separated into good and bad. And personally I just don’t.

I really do want to love Schur’s work. I like so much of what he does and how he does it plenty. There’s no question that I’ll be tuning in to see whatever he’s doing next. But it’s all had a suffocating faux-niceness that I can’t abide. There will be a lot of talk about loving people, about embracing all, but what he keeps showing us is that only certain people matter. In Schur’s world, the special people matter more than the ordinary populace. That’s not the world I live in and it certainly isn’t a world I want to. It’s a deeply cynical idea that presents itself as optimistic. I’d like to think that this isn’t intentional and Schur doesn’t personally believe this, but his art just doesn’t communicate anything else.

Gem of Amara is a newsletter written by Grace Robertson. She covers pop culture in various ways she sees fit, and it usually comes out on Mondays. If you haven’t already and would like this in your inbox, please subscribe.