Hey and welcome to more Lost reviews! As promised, we’re doing four episodes on the first Monday of each month, so let’s dive in! If you want this and other pop culture content in your inbox, please subscribe!

Tabula Rasa

Second episodes are hard.

“Tabula Rasa” is technically the third episode of Lost, but as the first thing produced after the pilot, it’s spiritually a second episode. The show has to restate the core themes of the pilot, underline what worked, and produce a first attempt at how this thing can work week-to-week. That’s always difficult, but it’s a nightmare here. Lost had a premise pilot, dedicated to establishing the set up, with no procedural aspect baked into the premise. The biggest mystery of the pilot wasn’t the monster, or the transmission, or the details of the plane crash or whatever. The real mystery was: how the hell are they going to turn this premise into an ongoing television series that can run for years and years?

It’s something that was a real struggle behind the scenes, as writer-producer Javier Grillo-Marxuach has documented in length (note: there are spoilers in that link). This could have been a show about the basic challenges of surviving on an island, or solving the supernatural mysteries, but that is not what a great television series has at its core. Great ongoing TV needs some kind of narrative engine producing story every week. “Tabula Rasa” had to answer the biggest question of all: what is this show actually going to be about, on a week-to-week basis?

Here’s what Lost is about. Each episode focuses on a single character, both in the present day on the Island and in their previous life through flashbacks. The character is in some way stuck in their lives, dealing with problems either of their own making or placed upon them, or both. The crash gives them a chance to start anew, a blank slate (hence the episode title). They will be able to take it and make the choice to save themselves, or they can fail to change, continuing their bad habits, and remaining “lost”.

Some of these arcs are already fairly obvious. Michael, having become estranged from his son, is being given the chance to reconnect and become a real father in Walt’s life. Charlie is going to have the chance to kick his drug habit (spoiler alert: he does not currently have access to an unlimited supply of heroin). Others are less clear right now, but all will form roughly this shape in time.

The show would challenge and subvert this theme over the course of its run, but when in doubt, it would always come back to this idea of people who are “lost” in their lives on the path to being “saved”.

So what of this instalment’s protagonist of the week?

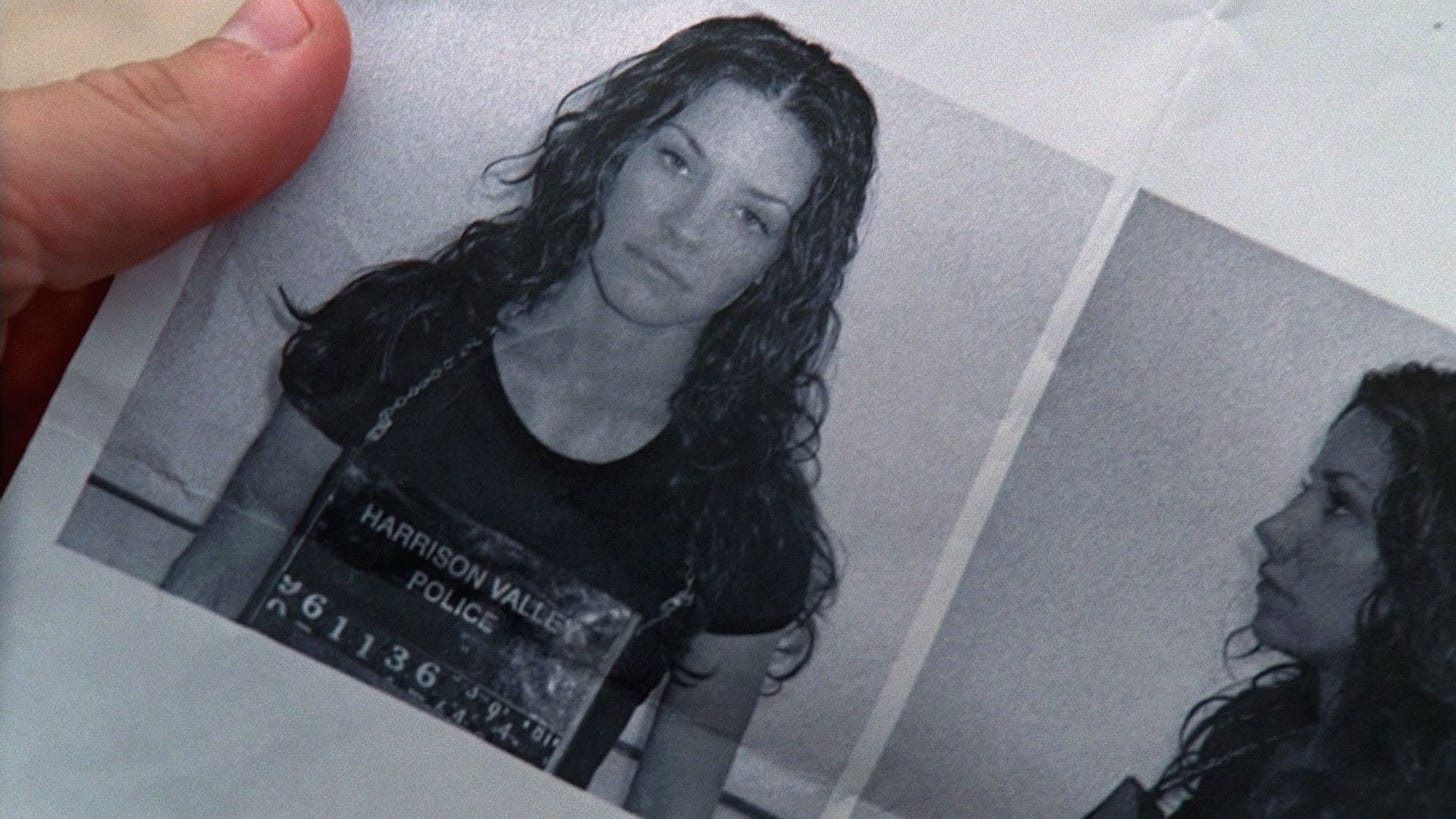

Kate is running. She’s in Australia because she’s always moving from place to place, taking up a new identity and hiding the truth. This is what Kate does. The Marshal, Edward Mars, being on her tail is what hangs over her, yes, but she still makes choices not to let people in. If she had tried to form a genuine bond with Ray Mullen out on the farm, perhaps he would not have turned her in. Perhaps he would have turned her in sooner. Either way, that’s not a choice Kate takes, because she’s a survivor. She’s got this far by shutting everyone else out, by lying, and by running as far as she can. Her mistake, as far as she’s concerned, is that she became too attached to Ray, and should’ve gone with her gut instinct to make a dash the previous night.

For all that one would expect Lost to be a show about survival, about doing whatever it takes to stay alive in the wilderness, the Island actually gives Kate a chance to stop surviving and start living. Jack offers her, in some fairly ham-fisted dialogue, the chance to start anew and forget the past. Edward Mars is dead. Whatever other law enforcement officers might be interested in her cannot, no way, no how, get to her on the Island. She can form genuine bonds with people, should she choose to. She might not take it. Her instinct to run, to detach, is strong, and there’s a version of her who ends up alone on the other side of the Island, desperate to avoid any kind of bonds, soon enough. But the crash has given her the option to grow and change. Salvation isn’t handed to anyone on Lost; they have to decide themselves worthy of it.

Now, if she’s going to be a person who connects with others, the question is about who she is going to be, and who she is going to connect with. It’s definitely a fair criticism of the way the writers handled Kate over the course of the series that she’s so often defined by the men in her life, and we can see the seeds of it here. But even so, it feels awfully enticing to have two versions of Kate personified by Jack and Sawyer. Lost plays with the idea of black and white a lot more than it actually embraces it as a philosophy, and even as it says Kate is either with the moral compass of Jack or the “just shoot him” mentality of Sawyer, it knows this isn’t how the world works. Sawyer and Jack have almost nothing to do with each other in the pilot, so this is the moment when the idea of them as two opposite forces is established.

Outside of Kate’s arc, we can see some of the show’s teething issues. It seems like they were still operating under the notion that all 14 series regulars would need something to do every week, which they thankfully moved away from over time. So we get a lot of subplots about adjusting to life on the Island. The most prominent, and best, of these centres on Michael’s attempts to find Walt’s dog, Vincent, in order to bond with his son, who grows closer to Locke. This is something the pilot hinted at that really grows here. It’s often easy to be frustrated by Michael as a character, but early on they really do get the balance right of centring his actions around the genuine desire to be the father he couldn’t in the “real world”. Otherwise, the only memorable moments are some nice first interactions between Charlie and Claire. If the cast were somewhat stratified in the pilot, they’ll need to mix it up as the show goes on, forming new dynamics and possibilities. With an ensemble this size, there are plenty of opportunities to mix it up.

“Tabula Rasa” is not a great episode of Lost. Everything it does will be done better later on. But it had the hardest of tasks in translating an event movie of a pilot into a workable TV series that can run for many seasons. In its success, every future episode of the show owes something of a debt to the work done here.

Notes

“Tabula Rasa” is written by creator/showrunner Damon Lindelof, this time in a solo outing, and directed by co-executive producer Jack Bender. Going forward, Bender is the man in charge on the ground in Hawaii, and the person most responsible for maintaining the series visual look from what J.J. Abrams established in the pilot. We can see the episode already experimenting with sound and visual cues to indicate the flashbacks already (they mostly just stick with the sound effect), while he’s figuring out how to light the scenes shot at night with only camp fires as the available light source.

Lost’s dialogue tends to be emotionally honest without exactly being poetry, and we already have some clunky but important lines like “Heard you tell the hero the same thing”

Sawyer’s hair has changed since the pilot, which obviously makes no sense within the context of the show, but it’s an improvement. He looks like Sawyer now.

Though he did not directly use the term, the concept of the tabula rasa, the blank slate, is most associated with the philosopher John Locke. Which brings us to...

Walkabout

Hi, I’m Grace Robertson and here’s a big theory about the television series Lost.

Most television series are shown from a subjective point of view. Buffy the Vampire Slayer, for example, is filtered through Buffy’s perspective. Her worldview is, broadly speaking, the show’s worldview. When she feels something is unfair to her, the show presents the events as unfair to her (which is why the infamous “Buffy gets kicked out” episode grates so much). Its spinoff series Angel, however, is from Angel’s perspective. It has a different view of the world because Angel himself sees it differently, in his weary old age, than Buffy. In the brief occasions where Buffy herself appears on Angel, she seems very unsympathetic because that’s Angel’s read of her in those moments.

Lost is certainly a show from a subjective view, but with one crucial difference: the perspective shifts between each episode. Lost is a Rashomon show. Each week, we see the events on the island as seen through the eyes of the centric character. This is why “Walkabout”, which uses Locke sparingly, is still indisputably his episode. Jack gets a similar amount of present day screentime, but it’s all filtered through Locke’s point of view. John doesn’t seem to have a high opinion of Jack’s leadership qualities, which is why he seems particularly irritable this time out. Kate seems much more capable in his eyes, and we see her in a much more positive light. It’s Locke’s island in “Walkabout”, just as it was Kate’s in “Tabula Rasa” and will be Jack’s in “White Rabbit”.

This is seen by many as the episode where Lost became Lost, and when people make this case, they’re almost always talking about the reveal of Locke’s wheelchair at the end. It’s a brilliant reveal that provides a physical metaphor for all of his life tragedies, but without defining him completely. An earlier draft of the script, written by Buffy and Angel veteran David Fury, didn’t even feature the chair. Locke’s tragedy is real even without it. He can’t escape the boxed in life he leads (I don’t think this episode mentions that the company he works for makes boxes, but it’s not really a spoiler to say it), a subordinate to a man half his age, relying on paying a phone sex operator just for an actual conversation. It’s the chair, though, that embodies it all. John believes the crash brought him back the use of his legs so he could truly go on this walkabout, to do what everyone told him he couldn’t. Last time, Kate couldn’t see the obvious truth that being stuck on the island was exactly the break she needed. This time, Locke is more than fully aware of it. It’s his destiny.

If Lost’s central theme is about characters choosing between moving past their problems on the island or getting trapped in the same bad habits, then Locke has no doubts as to which side he’s on. He’s often presented in contrast to the other survivors, desperate to get off the island and back to their failing lives, as the man who knows he’s in his element. Lindelof has often described the show about people who are metaphorically lost in life crashing on an island and finding themselves, goofy as it sounds. Locke is the only person on the island who feels like he’s seen the show.

While “Tabula Rasa” was Jack Bender’s first directorial outing, it’s in this episode that he really comes into his own. The central visual choice of this episode, to keep the flashbacks in mostly close-ups and awkwardly arranged shots to hide the chair, was forced upon him, but he makes it work in a way that feels like it’s gradually releasing tension. The office is shot with this very harsh artificial lighting, emphasising the unnatural cage that John lives his life in, which couldn’t contrast more strongly to the rich blues and greens of the island. It’s all very Wizard of Oz. The flashbacks might take place in the so-called “real world”, but nothing feels more dreamlike to John compared to how fully awake he is on the island.

Perhaps everyone was worried about suddenly giving over a full episode to a guy we’d barely seen up until now, or maybe they thought this was how the show would always work, but Jack has so much to do in this episode. It feels like it’s challenging the internal logic of the show with its central question: “why is Jack the leader?” On the island, he’s the leader because he was the guy pulling people out of the wreckage, the doctor who was the most useful survivor on day one, and no one gave it much thought beyond that. Behind the scenes, he’s the leader because he’s the protagonist, the white guy that ABC wouldn’t let Lindelof and J.J. Abrams kill off, and no one had a chance to think about it until here. It’s something that will be explored much more going forward, but this is the start of the idea that Jack might not be all that good at this. The hero stuff he can do, but connecting with the other people on the island is a nightmare to him. To quote everyone’s favourite comic book movie, “this is why Superman works alone”. Jack wants to pull people out of burning buildings. He doesn’t want to do the actual tasks of being a leader, like helping Claire organise a funeral ceremony.

They barely talk to each other here, but “Walkabout” in many ways is about presenting Jack and Locke as opposing figures. Jack as the man trying to keep the survivors tied to civilisation, making practical choices centred around the wreckage. Locke as the man fully immersed in nature. It’s here where so much of the show blossomed, and the episode hasn’t lost any of its magic in the years since.

Notes

The name “John Locke” is obviously a reference to the philosopher, and there was even an exchange between Locke and Kate cut from the script that lampshaded this. Lost was big on naming characters after philosophers and writers, it’s a whole thing.

We get another round of Shannon and Boone hijinks this time, with Charlie thrown in for good measure. Boone is keen to frame Shannon as incapable, whiny, and totally reliant on her brother but, oblivious to him, she’s already showing herself capable of existing in this society just as well as he can. And if we’re being honest, what Charlie does, getting Hurley to catch him a fish just because he wants to have sex with Shannon, is no better than Shannon doing it to prove a point to Boone. Shannon gets a bad rap, but I like her.

The characters are mingling more and more, with Claire seemingly taking on an important role as one of the more outgoing people on the island. The fun of having a 14 person ensemble is that you get to mix it up.

L. Scott Caldwell was never a series regular on Lost, and her other acting commitments meant Rose only ever appeared sporadically. But god, she’s so great in her scene with Jack here. A rich white male doctor from LA has no idea how to talk to someone like her.

I could not tell you what Sayid’s strategy to fix the transceiver was here, but at least it gave him something to do.

White Rabbit

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

Jack is the protagonist of Lost. He’s the leader of the survivors. The series opens with a shot of his eye. But that doesn’t mean as much as it might on other shows.

Take Breaking Bad, for example. Walter White is the protagonist of Breaking Bad and that show’s universe revolves around him. The other characters have internal lives, yes, but the choices they make primarily exist to serve Walt’s arc as the man who brought everything down. Breaking Bad is, before anything else, Walt’s journey.

Lost is not necessarily Jack’s journey. It’s the story of the survivors of Oceanic Airways flight 815, of which Jack is the first among equals. More often than not, he’s just the centre of the Venn diagram among the characters. If Sayid needs to communicate to Sawyer, say, well they both know Jack, so he’s who it’s going to go through. The show uses Jack as an entry point into the stories of everyone else. The closest comparison would be in how Orange Is the New Black (a clear structural child of Lost) uses Piper Chapman. In a big ensemble, someone has to be the keystone for all the other players to fill their roles properly.

These sorts of characters, the focal points around which a show is built, tend to infuriate audiences. It’s almost always more fun to hang out with Hurley or Locke than it is Jack. Everyone else gets to be more interesting while the keystone protagonist has to hold the show together. Matthew Fox had a thankless role on this show, with other characters getting easier, more entertaining work than him while he put in the hard graft. I’m loathe to overpraise him considering the noises about his personal life, but he really did do well as the centre of all this.

If Jack’s material in “Walkabout” was asking why he should be the leader on the island, then “White Rabbit” is here to answer in the affirmative. Jack, to borrow a line from the episode, has what it takes. Boone doesn’t have what it takes. Boone is desperate to be the hero of Lost, trying to save Joanna from drowning and getting Claire the water she needs, but he doesn’t have what it takes. He could never sell you on the big speech at the end. He couldn’t find the stream. Jack justifies why he is the leader and The Protagonist of this show. No one on the beach was able to step up and even try to rescue Joanna except Jack. If anyone is getting them off this island, it’s him. Lost is a show about characters from a bunch of different shows forced to exist on the same show, but Jack is the only protagonist in the bunch.

The meat of the conflict is obviously with his father, and to an extent I think this is slightly misinterpreted. Christian Shephard (his first name is not mentioned in this episode, but come on, it’s hardly a spoiler) is clearly a bad father. He’s an alcoholic who, based on the way Jack asks for a stronger drink on the plane in the pilot, has passed that trait onto his son. As we will see, so much of Jack’s weaknesses come from sins he’s inherited from his father. But, at this point in his life, he has what it takes. He lets Joanna die, but had he given his all to save her, Boone would have died as well. Hell, he would’ve died. He makes hard choices in this episode owing to his tough family life. But he does what needs to be done, and no one else on the island seems capable of doing that.

He’s lived in his father’s shadow, following the path set out for him. The conflict in Jack up to this point in his life is whether to follow this and become his father, or to reject him and be his own man. He can’t really do the latter, and it can only end up as him reacting to his old man. When he says at Sydney airport that he needs it to be done, he needs his father’s influence on his life to be done. It’s time for him to be neither his father’s son or the opposite. In smashing up the coffin on the island, he’s realising that he gets to decide when it’s done. He’s not in LA fulfilling his dad’s dreams of his son becoming a doctor anymore. Christian has never done anything like this. The island has given him an opportunity to finally become a complete, independent person.

This is a choice that Locke couldn’t take. Lost is obsessed with the idea of destiny, yes, but generally gives the characters a choice of which path they want to take. Jack and Locke both get their chances to be right and wrong, but in “White Rabbit”, there’s little doubt in my mind that Jack is correct. If Locke saw his father wandering through the jungle, he’d spend the rest of his life trying to figure out what it all means. It would consume his every waking moment trying to understand what it meant for his destiny. Jack is not Locke, and he just decides to smash the coffin and be done with it. He doesn’t care about divine intervention when his people need water to drink. He’s a practical leader, not a spiritual one.

While this episode is written by Christian Taylor and directed by Kevin Hooks (neither of whom became important voices on the show), the specter of Lindelof haunts it. Now, I’ve never met the man and couldn’t claim to have a huge insight into his state of mind in 2004. But here’s what we know. The behind the scenes stories at this point of the show are of Lindelof really struggling to come to terms with being the sole showrunner, the leader of Lost. He’s admitted to really struggling with the workload and stepping up to the plate, feeling like he was doomed to fail. And then you bring in the fact that his father, with whom he supposedly had a frosty relationship, had died two years earlier and, well, I guess I am psychoanalysing him now. But it’s hard for me not to watch an episode like this and not feel as though Jack is supposed to be Lindelof, intentionally or not.

At this point in, the show has spent less time contrasting Jack with Locke than it has Sawyer. And we get a little more of this. Everyone remembers the “live together, die alone” line, but it’s really Jack critiquing Sawyer’s approach to life on the island more than anything else. Lindelof isn’t exactly a dyed-in-the-wool socialist, but invoking a Billy Bragg song pretty much makes Lost’s position clear. As the edgelords would put it, the Lost characters live in a society. Jack “wins” this argument. The beach camp is collectivist.

Elsewhere, again we just get little snapshots of the other characters. It feels like the show is still figuring out how to integrate peripheral players in an episode that doesn’t have much to do with them, and the material mostly repeats things we already know. The exception is the aforementioned Boone, who really snaps into focus here. But Sun and Jin repeat the same note we’ve seen previously, while Sayid is mostly just defined as mildly irritable but competent at stuff. Hurley plays the part of The Audience, asking the questions we’re thinking, while Shannon feels weirdly “off” here. She’s materialistic, yes, but in other instances she’s not shown as stupid like she is here. It doesn’t feel quite right to me, though perhaps Jack just has a lower opinion of her. A lot of this all feels part of the very broadcast television desire to remind everyone of what’s happening week to week.

In his role as The Protagonist, Jack gets a lot of centric episodes, and many of them have a mixed reputation. But he gets off here on the right footing. We see Jack in clear focus here pretty much straight away, and this is a really strong, underrated episode of the show. I mean, it’d be special for the big Locke and Jack conversation alone, that I haven’t talked about enough, but there are so many classic nuggets of Lost that show up here. “Walkabout” made the show, but “White Rabbit” isn’t by any means a step down.

Notes

Michael Giacchino’s score sounds a little less orchestral than usual here. Presumably they were using different sounds to make the island feel more mysterious, but it didn’t really work, and thankfully it doesn’t stick.

The camera is really male gaze-y around Shannon’s legs in a way that’s hard to justify.

The search for water was also an early plot in Lost’s harder sci-fi 2000s cousin, Battlestar Galactica. It seems like something was in the, ahem, water.

More flashbacks than usual in this one, six instead of four. Perhaps they just felt the story needed to be told that way. It’s something they occasionally play with.

House of the Rising Sun

Sun makes a choice to stay with Jin.

This, to me, is the most important thing in the episode. It’s easy to imagine a version of “House of the Rising Sun” where she was set to run away after they landed in Los Angeles, only for the crash to force her to give her marriage another go. But that’s not what Lost does. In this show, she makes the choice to give it one more try, then the crash puts them into a space where they can genuinely start over. Of course, Jin has no idea any of this is happening, but “House of the Rising Sun” is not his story. We’ll get to him later in the season.

Everyone playing along with a Lost drinking game can take a shot in this episode because the root of Sun’s conflict in her life is, that’s right, her father. We don’t see Mr. Paik in this episode, but it’s laid out that he’s a wealthy man with less than legitimate business interests, who it seems has been a pretty firm patriarch over his daughter’s life. In broad strokes, Sun saw in Jin a man who represented none of this, and offered a very different kind of life. Until of course, her father remoulded him into his image, of a man “worthy” of Sun when she desperately wanted to get away from this.

This is the kind of fairly basic cliched stuff people point towards against the claim that Lost was a great character drama. It’s not difficult to find more complex portraits of human beings on TV than Sun and Jin. If you’re looking for the small moments of intricacy in the characters you might see on Mad Men or The Sopranos, you won’t find that here. But this is comparing apples and oranges, because Lost isn’t going for detail here. It’s a much more impressionist approach to characterisation, observing broad archetypes conflicting with each other. Lost is building from classic character types, putting them in entirely different contexts, rather than subverting those types within the individual people so much.

Once more, the Island offers them a choice to break their habits, to get out of the TV show they were on before. Neither of them have realised this yet, but for the first time since Jin went to work for Mr. Paik, Sun now has the power in the relationship. She is the one who speaks English. She is the one who would be just fine if they were to split up, the one who can interact with the other characters no problem were she to choose to. It’s Sun who resolves the situation with Michael through her communication. The power structure has been flipped. Of course, Jin has no idea of any of this. But Sun holds all the cards here.

The thing that makes “House of the Rising Sun” feel weirdly balanced is that the meatier story doesn’t involve Sun at all. The show at this stage seemed locked into the idea that if an episode’s A-plot was about someone else, the B-plot should centre on Jack. And our dear leader, bless him, is full of renewed energy and optimism after finding water and moving on from his father. The only problem is that he’s a terrible salesman. His plan makes obvious practical sense, as he lays out in the episode, and more importantly, the case for the beach is weak. The survivors can absolutely keep the signal fire burning with just a skeleton crew of people at a time, while everyone else is secure in the caves.

But it’s not about that. The new civilisation on the Island has its first culture war. One of the skeletons is carrying white and dark stones, taking us back to the pilot, but also as a visual representation of the caves against the beach. The beach, with its gorgeous sand and sea bathed in sunlight, feels hopeful, and represents a symbol of the real chance to find rescue. The caves are obviously dark and murky, but when you get in there, you’re admitting that you’re going to be stuck on this island for a long time. Jack has many skills, but PR is not one of them. He needed a pitch of hope when all he had was practicality.

Sayid’s motivations are still fairly opaque on this, and while we’ll get his story eventually, it’s not clear right now why he’s more concerned about hope than survival. The episode probably needed something a little more tangible on this. Michael has a clearly established motive with Walt, even as his terrible parenting on the Island suggests he’s totally unprepared to be a father in the real world. Kate, we already know, cannot stop running, even as she’s safe where she is. It totally works for her character. The caves are going to be a running thread, so everyone will be filled in a little more. And since this is a Sun episode, we really needed something to indicate why her and Jin made the trek, which we just don’t get.

Lost, thankfully, was made at a time when you could actually see what you were watching on TV, before everyone became obsessed with dimly lit scenes most people could barely make out. But the caves do pose something of an issue in this regard. I understand that the show wants to contrast them against the brightness of the beach, but it’s still difficult to see what we’re supposed to be looking at in some scenes. I don’t think the cave set ever looked as cool as everyone involved intended it to be, especially against the beauty of Hawaii in all its natural glory.

The other major story here is between Charlie and Locke. I really like the way this further elevates Locke as the Island’s spiritual leader, in his role guiding Charlie away from the drugs and toward something constructive. As much as he dresses it up, he’s not actually doing anything mystic here, but it’s in language that Charlie finds important (again, the show is contrasting Locke with Jack, who can’t speak people’s language). The introduction of the guitar as a motivation for Charlie feels out of nowhere, but it’s not like it isn’t something he would care about. It works well enough, though they really could’ve planted the seeds better earlier. This is not a good episode for Charlie, who seems especially incompetent from the bees onwards. But again, it’s bringing the core theme of Lost to the fore: Charlie has a choice.

I like all the pieces in this episode, but I really do wish the show had found a way to centre Sun better here. The twist that she speaks English is badly needed going forward just to integrate her and Jin into stories with the other characters. As it is, they’ve felt very isolated, and this is why it must have been so hard to build an episode around them. As the opening shot established, Sun has been a peripheral player on the island. Putting her front and centre was something we needed to see, but also felt narratively messy.

Notes

This episode was written by the great prolific genre TV writer-producer Javier Grillo-Marxuach. He’s written a lot about the show online, and I’d highly recommend checking it out (though it has spoilers abound).

The episode was directed by Michael Zinberg. This is his only Lost episode, though he’s worked on a lot of different types of TV shows. I really love the way he shoots Sun listening in on Jack and Kate’s conversation, giving us an early clue that she does speak English.

Jack’s tattoos honestly sound like a fun tease here

Giacchino’s theme for Sun is a great, underrated part of the Lost music canon

I can’t tell, but the internet reliably informs me that Daniel Dae Kim is not a fluent Korean speaker. I’m sure it would be very grating if I were able to understand the language.

Yunjin Kim, of course, is very much a native Korean speaker, and she’s really fantastic in the role. A consistent ace that the show could turn to, in my view.

We don’t get any dialogue from Claire, Shannon or Boone this week. The show is beginning to trust that the audience don’t need reminding of everyone on the island in each episode.

Spoilers Ahead

That almost every Kate flashback follows this same structure lessens “Tabula Rasa”’s effect rather a lot, but that’s not on this episode

“Walkabout” might pretend we don’t get a shot of the monster, but of course the Man in Black is right there appearing as Christian Shephard. Though surely unintentional, it’s a great bit of foreshadowing to see him disappear just as Locke arrives with the boar.

Jack is terrified of what he’s seen on the island (his dad). Locke says he’s looked into the heart of the island (the monster), and what he saw was beautiful. They are looking at THE SAME THING.

Sun is supposed to leave at 11.15. 11 is not one of the numbers, but 11 o’clock in Sydney is 4 o’clock in Los Angeles.